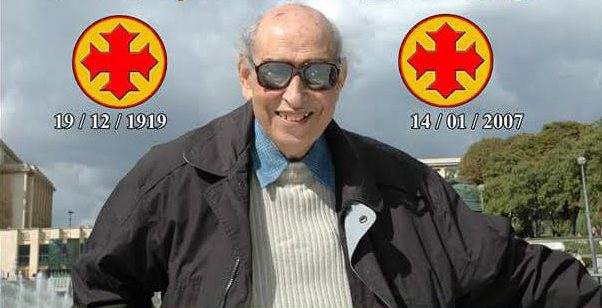

He is famous as the pioneer of the modern form of an ancient art, that of the Coptic icon. This is an art that drew on ancient Egyptian artistic tradition and went on to refine it in the Christian tradition throughout long centuries. It took Isaac Fanous (1919 – 2007), though, to bring it into modern form.

On 21 January 2023, the Lovers of Coptic Heritage Society (LCHS) held a seminar, sponsored by Pope Tawadros II, at the church of the Holy Virgin in Ard al-Golf in the eastern Cairo suburb of Heliopolis, titled “Isaac Fanous … Pioneer of the art of the icon in modern times”.

The Lovers of Coptic Heritage Society was founded in 1998 with the aim of raising awareness of the value and beauty of Coptic Christian heritage, especially in its wider Egyptian context.

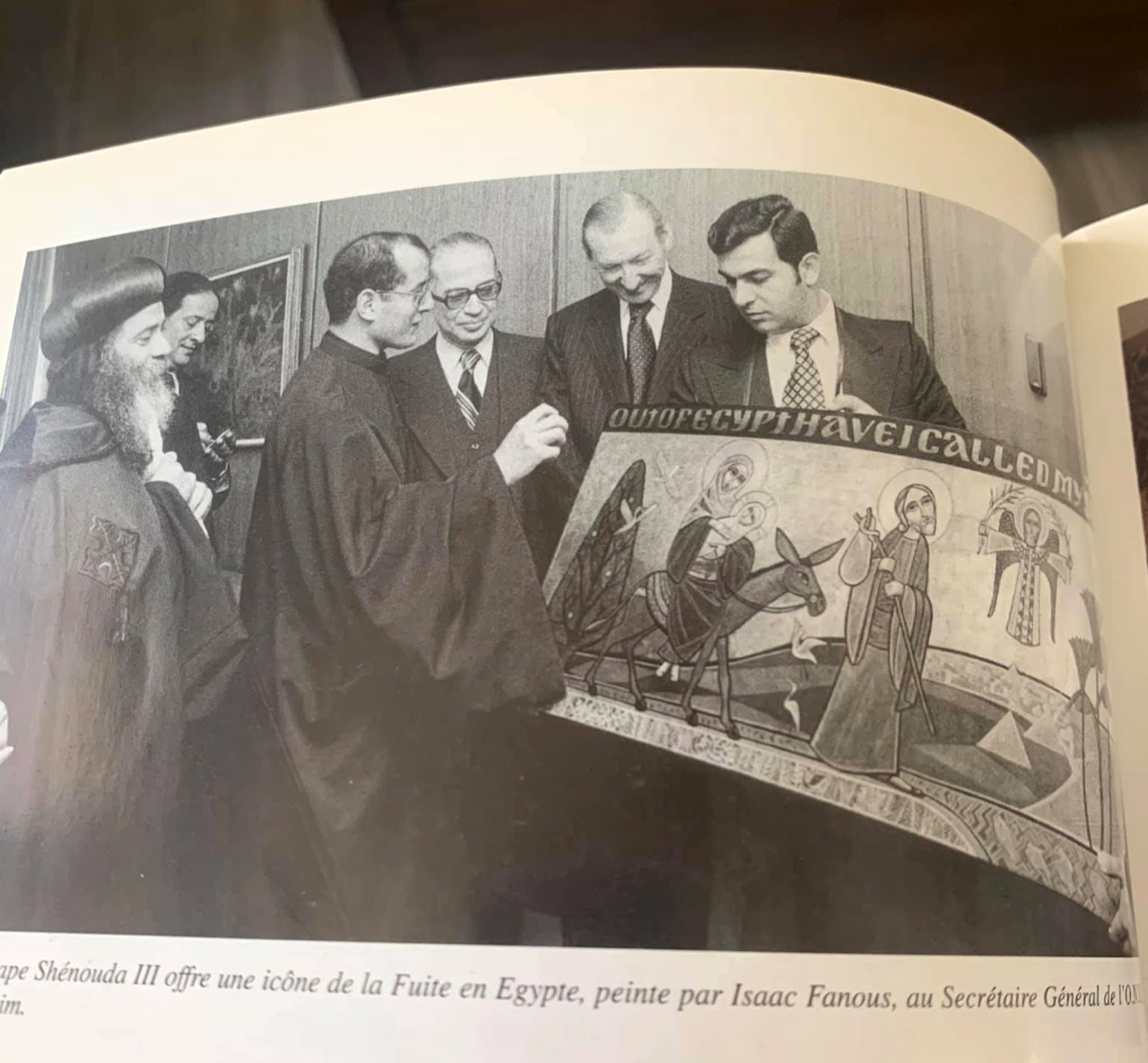

Icon gifted by Egypt to UN

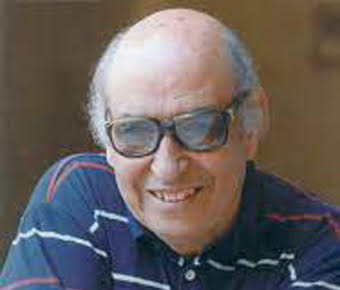

Isaac Fanous was born in 1919 in Maghagha village some 212km south of Cairo. He went to school in Cairo, graduating with a degree in Applied Arts in 1941, and another in Art Education in 1943.

Mr Fanous was introduced to Marcos Pasha Simaika (1864 – 1944) who founded the Coptic Museum in Cairo in 1910 and was its director. Recognising Fanous’s artistic talent, Simaika offered him a job at the museum where he mingled with great Egyptian specialists in Coptic art and culture. He enrolled in the Institute of Coptic Studies in Cairo (CSI founded in 1954) earning a doctoral degree in 1958. In the mid-1960s, he went to Paris on a two-year study grant at the Louvre. While there, he studied icon painting under Leonid Ouspensky, eventually developing a style that was to become the new face of modern Coptic iconography.

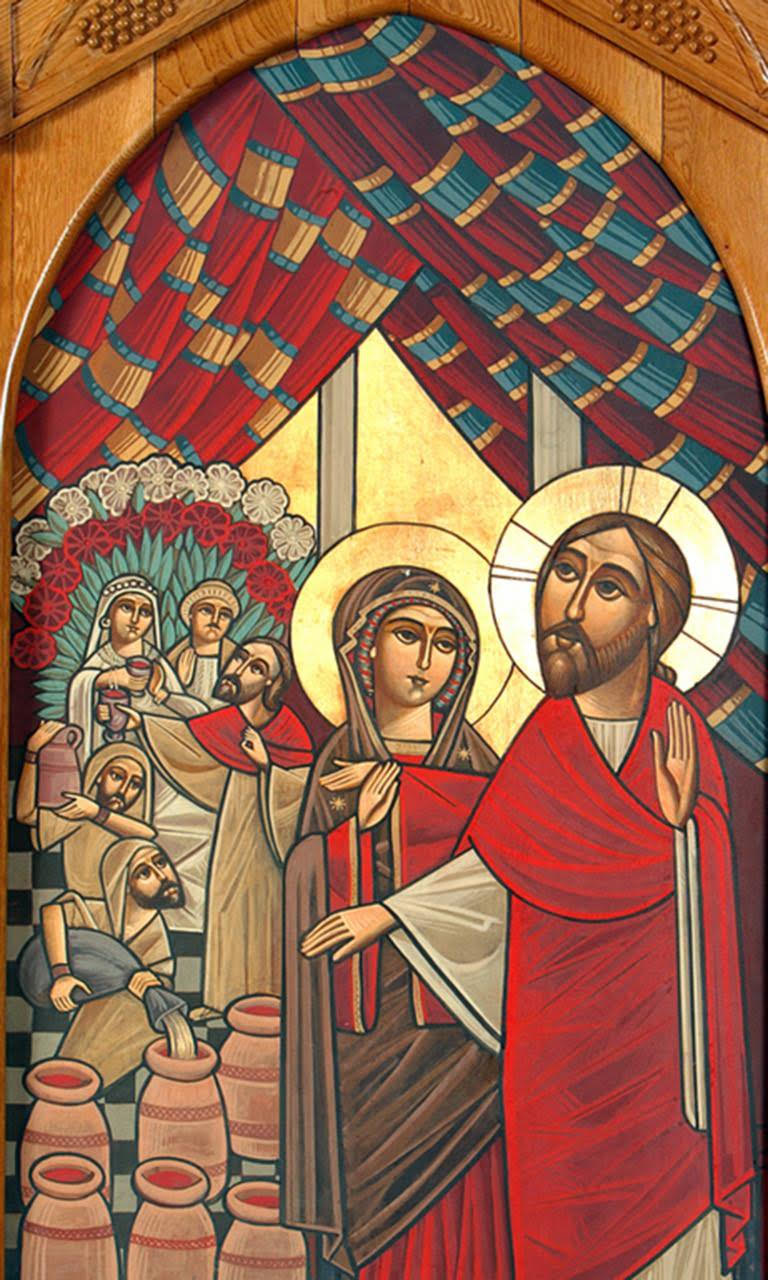

Back in Cairo, Dr Fanous started what was to be a long, spectacular career of writing icons, making mosaics, and painting frescoes inside and outside Egypt. His works hang at the churches of the Holy Virgin in Ard al-Golf and in Garden City in Cairo; the shrine of St Mark in Abassiya, Cairo; also at the Catholic Church in Cairo’s Nasr City. He wrote the icon gifted by Egypt to the United Nations in 1978.

He is famous for using traditional materials and paints, also for using the same old time-honoured method of icon painting.

Dr Fanous chaired the Coptic Art department at the CSI from 1977 till his death in January 2007, where he trained numerous young Coptic iconographers from inside and outside Egypt. His many awards include an Egyptian Encouragement Prize in 1956, and an honorary doctorate for lifetime achievement in 1984 by Pope Shenouda III, and a golden medal by the Venice Oriental Studies Institute in 1987.

Non-religious works

The recent seminar started with a word by Samy Mitry, founder and head of the LCHS, who said that the Society was this year celebrating its 25th anniversary with a series of events that focus on Coptic Art. He introduced Isaac Fanous’s family, his siblings and their children, who were attending the seminar—Dr Fanous had no children; also a number of his iconographer students among whom were Galal Ramzy, Martha Naim, and Mary Girgis, who paid him tributes during the seminar.

Samy Sabry, renowned expert on Coptic architecture, said that Dr Fanous had founded a great school of art, and reminded the audience that they sat in the church of the Holy Virgin in Ard al- Golf, surrounded by his great icons and mosaics.

Galal Ramzy, who designed and painted the icons of the Cathedral of the Nativity of Christ in Egypt’s new administrative capital, was a faithful student and colleague of Dr Fanous, knowing him from their school days and closely working with him from 1961 to 1990.

Not many may know, Mr Ramzy said, that Dr Fanous had accomplished many non-Coptic art works, a number of them are now housed at the Egyptian Museum of Civilisation in Cairo. He also worked with cinema director Cecil DeMille in preparing the scenery for the 1956 film The Ten Commandments.

Mr Ramzy talked of an incident that occurred at the Louvre, where a group of restorers had been working to reassemble pieces of stone into their original form as an ancient Egyptian stele. Dr Fanous joined them and, leaning on his Egyptian backdrop and his study in sculpture, was able to offer so much expertise that, once the stele was successfully reassembled, he was asked to join the group, and remained with them till he went back to Egypt in 1967.

Conserving heritage by using it

In Egypt, Mr Ramzy recalled Dr Fanous’s first works at an Alexandria church, then other works in Cairo and other places. “At the time,” he said, “we became very close, and I became his student together with many others who went on to become pillars of modern Coptic iconography, including Bodour Latif (1921 – 2012).

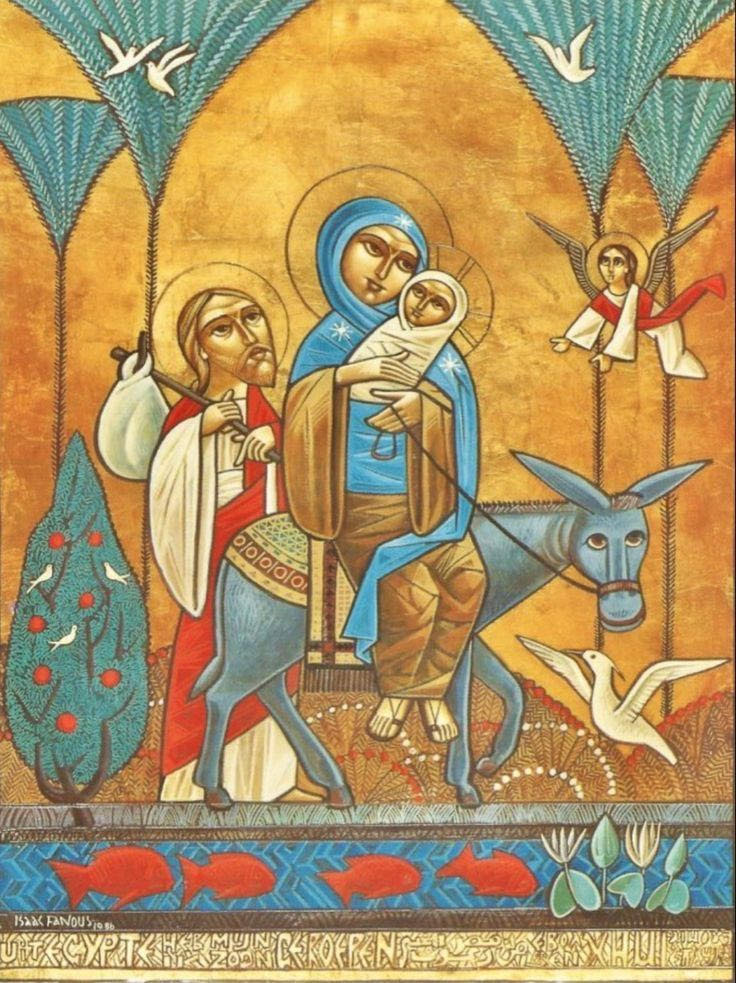

“We became constant companions, and he asked me to join him in his works, especially when he had concurrent assignments in different places. At one point he had to do a Last Supper icon in London and another in Tanta, Egypt; a third icon in a church in Shubra, Cairo; and a fresco at another Shubra church. We also made a plethora of frescoes that included the Nativity; the Flight into Egypt; the Epiphany; St Peter about to drown; Jesus’s Entry into Jerusalem, His trial, Crucifixion, Resurrection, Ascension, and many others.

“It was a significant day for Dr Fanous when, in 1974, the Italian Culture Minister sent a message to the CSI and museum curators in Cairo, asking about the best way to preserve heritage. The almost unanimous reply he got was to conserve it in museums. Dr Fanous, however, begged to differ. He said the best way was to make heritage live on by exploiting it in modern works based on it. He presented a study in 10 pages, citing examples of how the prominent characteristics of ancient Egyptian art were being used in creating modern-day icons. Italy’s Culture Minister was so impressed that he invited Dr Fanous to Italy in his capacity as a reference to that school of thought in art. He was given an honorary doctorate.”

Reflecting the light

“In Cairo, the Coptic Pope Shenouda III granted Dr Fanous an honorary doctorate for his achievements at Cairo’s CSI. In this, Dr Fanous was one of the first four Copts of singular achievement to be granted honorary doctorates by CSI; the other three were Ragheb Moftah, the first Copt to transcribe Coptic melodies into musical notation; Shaker Basilios, professor of Coptic language; and Photography professor Anis Rizkallah.”

The years passed, Dr Ramzy said, and Dr Fanous was asked by Egypt’s Antiquities Authority to make an 11-metre long fresco at the carriages museum in Cairo’s Saladin citadel. No other artist had agreed to do it; I joined Dr Fanous in that magnificent work. He also did another splendid work in Cairo, a mosaic with the prominent Egyptian artist Salah Abdel-Karim (1925 – 1988), which still stands today in Cairo’s main railway station.

Mr Ramzy continued with describing works he had done with Dr Fanous till they parted in 1990 because Mr Ramzy had to leave Egypt. He concluded: “Dr Fanous was an artist who had immeasurable pride in his Egyptian roots and Coptic art. He would work in silence while listening to Coptic melodies. He had profound faith, and was confident that God managed his life and his every move, and protected him from all evil. In truth, Dr Fanous’s life reflected the light of the icons he wrote, emanating love for all around him.”

Beautiful spiritual condition

Mary Girgis was a student of Dr Fanous. She spoke of her first experience with him as a very young trainee. “I was in awe of that great master, given that I was the youngest of his students, and he was strong and sharp. With the first argument I burst into tears and rushed out. But he looked for me and gently explained his viewpoint, tenderly kissing my head. Since that day, fear had no place between us.”

Professionally, Ms Girgis said that at Dr Fanous’s hands, she gained boldness. “He taught us not to use pencil when designing, but to use charcoal instead, and not to hesitate as we made decisions.” She said that he taught them as well the vital importance of accuracy when creating an icon, requiring us to read the Bible very well to be able to depict even the minor details.

“On the spiritual level,” Ms Girgis said, “Dr Fanous taught us how to love God and how to pray before starting on any icon. We learned to live a beautiful spiritual condition in our iconography work.”

No one like another

Ms Girgis explained that Dr Fanous was heavily influenced by ancient Egyptian art. This manifested in his icons: the long ancient Egyptian-like hands of the Holy Virgin when holding the Child Jesus; the concept of magnification of the major faces or elements and reduction of the minor ones in the two-dimensional icon art, and the principle of transparency where hidden elements are depicted as visible.

Dr Fanous, Ms Girgis explained, was influenced by contour drawing, one of the features of Coptic art. The purpose of contour drawing is to emphasise the mass and volume of the subject rather than the detail; the focus being on the outlined shape. He depicted the focal characters in the centre of the icon, while secondary characters are depicted on the sides.

As to depicting faces, Dr Fanous would draw the wide shaped almond eye to indicate spiritual awakening; the small smiling mouth; and hair styled in various ways such as straight or curly.

Dr Fanous also tended to depict the faces of the important characters as facing the viewer, while those of Roman soldiers, Judas, or evil persons were inclined or in profile. He would fill the spaces in the icon with colour, using light lines side-by-side with the bold outlines, to emphasise the beauty.

“Among the most remarkable features of Dr Fanous was that he insisted on giving each and every icon a unique individuality. None was repetitive or a reproduction of another; in icons depicting the same topic, he would retain the depiction of the main elements but change the details so that no two icons were ever the same.”

Unlike the icons

Ms Girgis explained that Dr Fanous mastered the art of frescoes, which is not at all easy given that it involves the use of oxides that are dissolved in water and painted directly on the wall. There is no chance for an iconographer to re-paint or remove what he or she has done.

Contrary to painting icons, which starts with the darkest colours then increasingly moves on to the lighter ones, frescos begin with application of the lighter colours and moves on to the darker. This process gives an extremely rich gradation of colours and a beautiful shine to the faces in the icon.

Interpretation of the Bible

Martha Naim was also student of Dr Fanous, starting 1986. “Dr Fanous knew very well how to guide us to create artwork; each according to their specific talent,” she said at the LCHS seminar, “all while humbly respecting our own visions.

“In my case, he would assign me to work on mosaic portraits, calling me a ‘portraitist’. He had a special method in making any design; he would start with the total mass, then abstract it.

“We learned from him patience and persistence, especially when working on mosaics because they take a long time to complete; sometimes weeks and months on end.”

Dr Fanous was multi-talented; he was a sculptor; restorer, iconographer, mosaic and fresco artist, Ms Naim said. “He created aesthetic values of the many saints he depicted. In his hands, the lines and contours, light and shadow turned into meanings, symbols and feelings; his icons were pure and perfect.

Ms Naim described Dr Fanous as a well-organised person who kept his tools clean, and was punctual in his appointments. He had a strong memory, and was very secretive about the charity work he generously did.

“We learned from him the importance of being quiet, listening to music. In his atelier, we heard nothing but the soft tones of music.

“Despite the many awards he had received, Dr Fanous branded himself simply as ‘one who spent more than 50 years of his life an artist who never laid down his brush’.”

On the human level, Ms Naim said, Dr Fanous was “a kind father to each of us; he gave us advice, and taught us to take care of one another.”

Ms Naim teared up as she concluded: “He left a great void. Working with him was not merely about doing art, it was about doing Christian art as an interpretation of the Bible.”

Watani International

1 February 2023

Wow, incredible weblog layout! How long have you been running a blog for?

you made blogging glance easy. The overall glance

of your web site is wonderful, as smartly as the content!

You can see similar: Zaraco.shop and here https://zaraco.shop