As matters stand, the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) continues to be a bone of contention between Ethiopia and Egypt. Granted, Ethiopia desires to use the dam as a means of direly needed development, but for Egypt which has practically no water resource other than the Nile, the Nile waters constitute the country’s lifeblood.

Water scarcity

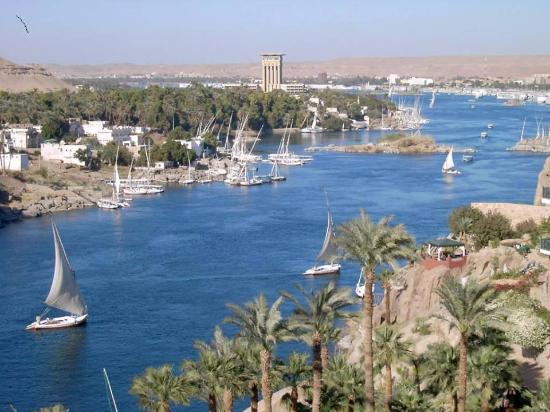

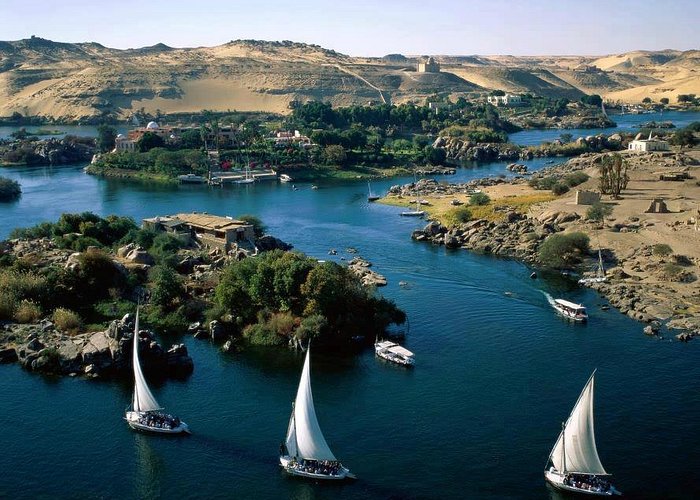

Ethiopia started building the dam in 2011 at a time when Egypt was in the throes of the so-called Arab Spring. Egypt had always objected to building the dam which straddles the Blue Nile, one of the main tributaries of the River Nile, on grounds that it would reduce the amount of water flowing into Egypt which is technically a desert that gets next to no rainfall and depends on the Nile for about 96 per cent of its water resources. Ethiopia however claimed that the dam was not for water storage, but was a huge hydroelectric power project that would not affect Egypt’s share of water. Egypt claims that this is not strictly true, and definitely does not apply to years of lesser rainfall on the Ethiopian plateau during the rainy season. It is this rainfall that causes the annual flooding of the Nile and provides the bulk of waters flowing into Egypt.

The potential reduction in the Nile water flowing to Egypt comes at a time when the country is significantly dropping below the water poverty line and approaching the absolute scarcity limit (560 m3/capita/year).

International law and relevant treaties underscore the importance of coordinating the use of watercourses between upstream and downstream countries.

GERD has a concrete volume of 10.5 million cubic metres, and stores water in a 74-billion-cubic-metre reservoir that can theoretically store as much water as the total annual share of Egypt and Sudan combined. The reservoir stretches on a 1,800-square-kilometre area, resulting in enormous evaporation and seepage losses in addition to possible upstream usage.

Intransigence

Once Egypt rid itself of the Muslim Brotherhood regime that had come to power in the wake of the Arab Spring, and settled down into a civil State in 2013 / 2014, serious thought was given to the GERD issue. Egypt made it very clear that it recognises Ethiopia’s development needs as embodied by GERD, but that it requires close collaboration between the three riparian countries—upstream Ethiopia and downstream Sudan and Egypt, to avoid significant harm on the downstream riparian States.

In March 2015, Egypt, Sudan, and Ethiopia, signed in Khartoum a Declaration of Principles to serve as the basis for negotiations among the three countries over the filling and operation of GERD. The agreement asserted that cooperation between the three countries should be based on “mutual understanding, common interest, good intentions, benefits for all, and the principles of international law.” It also stated that guidelines on the first filling of the GERD reservoir should be developed as the dam was being constructed. However, since signing the declaration of principles, Ethiopia has essentially acted unilaterally regarding the filling and operation of the dam.

No agreement materialised despite multiple rounds of negotiations, and even attempts by Egypt to resort to international experts on the matter. All through, Ethiopia adopted an intransigent attitude, refusing to cooperate or to supply the international experts, who it had selected, with any information they required. It became obvious that whereas Egypt and Sudan sought a legally binding agreement on the filling and operation of the GERD, Ethiopia preferred a set of non-binding guidelines that could be modified at any time.

Existential threat

Egypt, which has repeatedly said that it regards threats to its water source as an existential threat, took the matter to the UN Security Council in July 2020 and again in 2021. The UNSC, however, declined to issue any resolution, deciding that the matter could be resolved through negotiations sponsored by the African Union. Again, Ethiopian intransigence prevailed and no agreement was reached.

In the meantime, construction of the Dam was never halted. In summer 2020, Ethiopia unilaterally executed the first stage of the reservoir filling, and continued with the unilateral filling during the summer seasons ever since.

As summer 2023 approaches, Ethiopia will be ready for the fourth filling. A recent official announcement that the country has now completed construction of about 90 per cent of the dam has outraged Egyptians; even though the information was in no way unexpected, it was a stark reminder of the unilateralism embraced by Ethiopia.

Incalculable suffering

Hani Sewilam, Egypt’s Minister of Water Resources and Irrigation, remarked that Ethiopia’s persistence in unilaterally operating GERD while rejecting any cooperation with Egypt, stands to jeopardise Egyptian economic and social stability. He said that Egypt is committed to joint cooperation through negotiations based on sound studies, in order to secure fair usage of the Nile waters. This, he said, would work to alleviate hazards, and would be a win-win situation for all involved. “Egypt is almost exclusively dependent on the shared waters of the Nile, and has thus always been keen on cooperation and coordination with the other riparian States.” He stressed that uncooperative, unilateral procedures disregard international law, pointing at the absence of negotiation and a binding agreement on operation of the dam, also at the lack of studies on GERD’s environmental, economic, and social impacts ever since and even before the unilateral project started some 12 years ago. “Even so,” Mr Sewilam said, “Ethiopia continues to fill it and operate it in total disregard of international principles and agreements on shared natural resources.”

It is frequently claimed, Mr Sewilam said, that hydroelectric power projects pose no hazard, but the fact is that in the event of several seasons of drought—a not unprecedented situation—with no binding agreement in place to make provisions for that event, Egypt would suffer incalculably. A large portion of the country’s arable land would be ruined, he said, and millions of Egyptians would be out of work.

Sceptical about figures

Abbas Sharaky, Professor of Geology and Water Resources at Cairo University, is sceptical about the figures announced by Ethiopia. He says that the 90 per cent GERD completion figure is overinflated, and puts the actual completion figure at 78 per cent: 85 per cent of the concrete works and 70 per cent of the electric works. He bases his estimate on figures posted by the firm We Build which executed the concrete works of the GERD project. We Build has posted that 1.6 million cu.m of concrete work have not been executed out of a total 10.4 million cu.m, which means that 85 per cent have been completed. As to the electric work, only two turbines have been installed so far out of a total 13.

Turbine installation, Dr Sharaky says, is a time-consuming process that requires utmost precision; the two turbines in operation now took more than two years to install. In addition, he says, satellite photographs of the GERD site show limited operation of the turbines.

Ethiopia’s official GERD figures, Dr Sharaky believes, target the Ethiopian public in the first place and have, more often than not, been inflated to rally that public.

Cross-border river

For Nader Noureddine, Professor of Water and Land Studies at Cairo University, and strategic expert at the Food and Agriculture Organisation, the Ethiopian official figures come as no surprise.

“Ethiopia’s claim of having completed construction of 90 per cent of GERD” he says, “is no more than part of the squabbles that occur every year once the time of the new filling approaches. It is a naive provocation, since both Egypt and Sudan approved the dam construction and its storage capacity in the Declaration of Principles signed in 2015.

“Ethiopia claimed it does not recognise the historical water shares of Egypt or Sudan, nor the colonial era agreements signed between the countries. Again, this reflects political naïveté, given that, legally, there is no such thing as ‘historical’ rights. Rather, they are acquired rights to waters that reach downstream countries by virtue of the natural downward slope of the course of the river. Egypt has been getting these waters throughout millennia, a fact that has nothing to do with ‘colonial-era agreements’. Ethiopia can take no credit for being the land of the river source, nor can Egypt be blamed for being the home to its mouth.”

Dr Noureddine stresses that both Egypt and Sudan have the right to know in advance the volume of waters that would reach them every year. Operation of the dam and turbines ought not be a unilateral Ethiopian affair since it directly affects their partners in the river waters. After all, Dr Noureddin says, the River Nile is a cross border river, not one that is limited to Ethiopian land.

“Ethiopia and the African Union,” he says, “have disregarded the UNSC decision to resolve the GERD issue in a manner that is adequate and binding to all parties.”

Watani International

3 April 2023