Who’s the most important figure in a village? Ask anyone that question and the reply you’d most likely get is: “The Mayor”. Correct, regarding Egypt as much as practically everywhere in the world. Seeing that rural communities in Egypt are widely conservative, mayors have traditionally been men; the job was off-limits to women. A law in 1994 changed that however, allowing women to run as candidates for mayoralty; the Interior Ministry appoints the person it sees as the fittest candidate.

Egypt includes some 4,496 villages that vary in size and population; not all have mayors. Ever since Egypt had a modern police force in the mid-19th century, the larger villages featured a police station, rendering redundant the traditional mayor whose job goes back in time to ancient Egypt. Yet among the thousands of smaller village mayors in Egypt, only four are women. The first was the Copt Eva Habeel Kyrillos, born 1955, who in 2008 became Mayor of Kombouha in Assiut some 350km south of Cairo. Watani covered her story.

The Egyptian mayor is the venerable, all-significant Omda, a figure that commands respect given that he—or she for that matter—has a function socially ingrained in Egypt’s rural community. He is the liaison between the government and the villagers, has a pivotal role in solving conflicts and settling disputes, and is in charge of security.

Why the long introduction? Because a recent TV drama aired by al-Hayat satellite TV channel last Ramadan—the Muslim holy month of fasting, that is also associated with love of entertainment and hence features the best TV shows—broached the topic of a female Omda.

Thorny issues

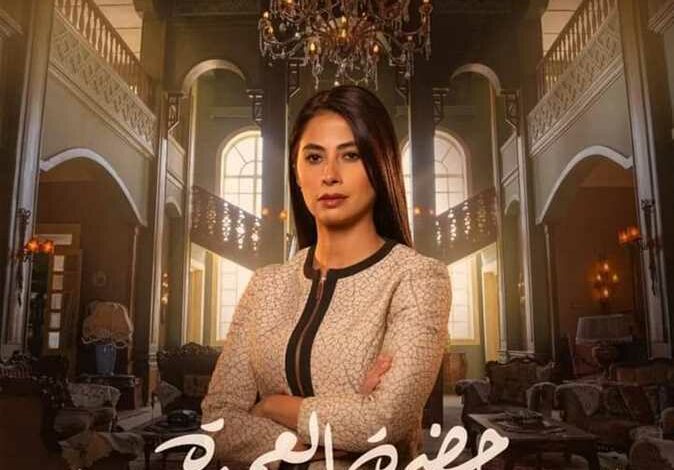

The TV drama, which came under the title Hadret al-Omda (Her Excellency, the Mayor), was written by writer, journalist, and media personality Ibrahim Eissa who is famous for his liberal views. It was directed by Adel Adib, and starred singer actress Ruby as Mayor.

“Our society will improve when women lead. This is a principle I firmly hold,” Mr Eissa said in an interview hosted by Lamees al-Hadidi on ON TV channel.

“Decades ago, the law allowed women to run for mayor, yet today we have a mere four female mayors out of some 4000.”

Mr Eissa’s Hadrat al-Omda focuses on women’s issues, aiming to empower women by seeing them successful in important positions.

His mayor Safiya al-Faris is in her 40s, and teaches psychology at the American University in Cairo. Her family pressures her to return to her home village Tall Shaboura where they live in order to run as candidate for mayor, since they believe she is capable of taking action to solve problems in the village.

Ms Faris complies, and succeeds in getting appointed to the post, only to find herself directly faced by numerous challenges; not least many them is that many in the village cannot accept a woman as mayor. Once she persuades them she is entitled to a fair chance to shoulder responsibilities, she embarks on tackling the most flagrant of the village problems. Here, Mr Eissa introduces a Pandora’s Box of an intricate web of social and economic problems, to say nothing of sectarian undercurrents, that Ms Faris has to deal with. She needs to tackle illegal emigration, outlawed excavation for antiquities, child marriage, all forms of violence against women, female genital mutilation (FGM) commonly known as female circumcision … all of which are rampant common practice in the village.

Round of applause

Hadret al-Omda Ms Faris clearly aims at moving the villagers of Tall Shaboura into a decent life. This feat can only be achieved through changing thoughts and attitudes as well as means and infrastructure.

The Omda’s efforts against FGM brought on a round of real applause from the National Council for Women (NCW). The Council’s President Maya Morsy wrote on Facebook: “A salute to the Mayor, who stands in the face of the crime of female genital mutilation, with dialogue written in a very professional manner.” She commended Ibrahim Eissa and Ruby. “Your Excellency the Mayor,” Ms Morsy wrote, “that was a very, very honest scene.”

A first in sectarian attitude

For the first time in Egyptian drama, the show Hadret al-Omda realistically tackles the issue of the fundamentalist Islamic thought used to deny Christians their right to worship.

Mr Eissa exposes the common practice by religious fundamentalists, especially in rural Egypt, to persuade Muslim villagers to ban Copts from holding prayers; also their violent protest against the right of Copts to build a church.

Previous TV or media drama usually depicted Copts as living smoothly alongside their Muslim neighbours, whitewashing the bitter discrimination and violence Copts were subjected too in many rural or poorly educated neighbourhoods where Islamic fundamentalist thought prevails. Such drama shows disregarded the real problems that frequently caused rifts in relations between people of the same locality, and led to extremist actions that sought to destabilise Egyptian society.

Hadret al-Omda shows a typical situation where the village Copts, visited by a priest, hold prayers inside a house belonging to one of their elders because there is no church in their village. Once the Muslims learn that a priest is in the house, they march to it and warn the Copts they are not to pray inside the village. They surround the house, terrifying the Coptic women and children. Anxious about what may happen to their priest, the Copts try to smuggle him out with the help of a moderate Muslim villager.

Harassment of Copts

On Christmas Day, the Copts gather in the Coptic elder Amm Hanna’s house to wish him well and to meet the priest who had come to wish them a happy Christmas. The fanatic Muslims learn about the gathering, and rushed to Amm Hanna’s house with guns and sticks, intending to attack the Copts. Some villagers rush to the Mayor with the news, she gathers a group of young enlightened youth and heads to Amm Hanna to confront the rioters. The Omda asked the rioters why they surround the house, they reply claiming they were there to prevent building a church in the village. However, their planned attack having been aborted, the extremists have no way but to leave.

Ms Faris counters the damaging fanatic thought that destabilises the village with bringing in an enlightened sheikh to lead the village mosque and spread tolerant thought.

In another incident, the Mayor discovers while on a visit to the village school that one Coptic pupil was wearing higab (hijab), the Islamic veil. Surprised, she asks her why? The girl says that the headteacher, a fanatic Muslim, ordered all girls to wear higab as part of the school uniform. Since no law condones the enforcement of higab, the Omda sees to it that it is donned only by girls who choose to don it. Again, she counters fanatic thought with the tolerant acts of the enlightened youth.

Ultimately, the Omda is able to lead the villagers to collaborate to make their village a bright, peaceful place.

Watani International

8 May 2023