Given that Watani International is this year marking 20 years in print—our first issue was printed on 18 February 2001—we have promised our readers to publish every month a review of our issues in two successive years. We already reviewed the issues from 2001 to 2010; today we keep good on our promise by covering 2011. That was the year of what came to be termed the “Arab Spring”; a year so eventful that we will cover it alone in this issue. Just as the other reviews, it reads as history in real time.

New Year bomb blows Copts up

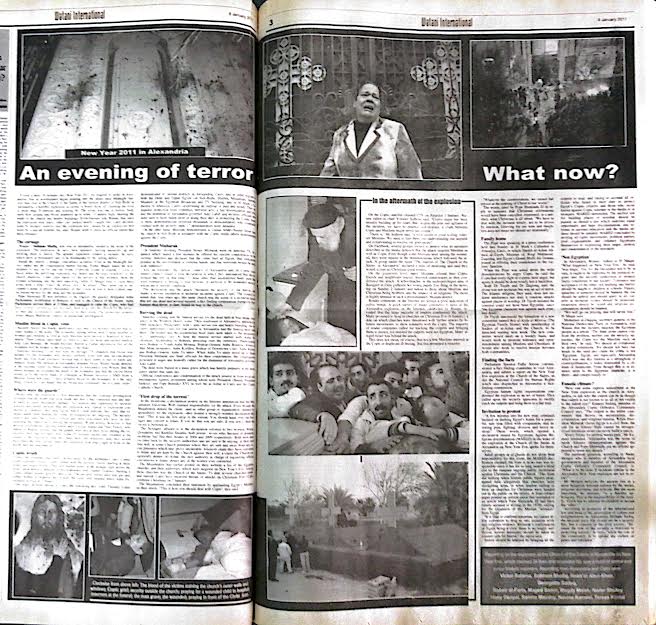

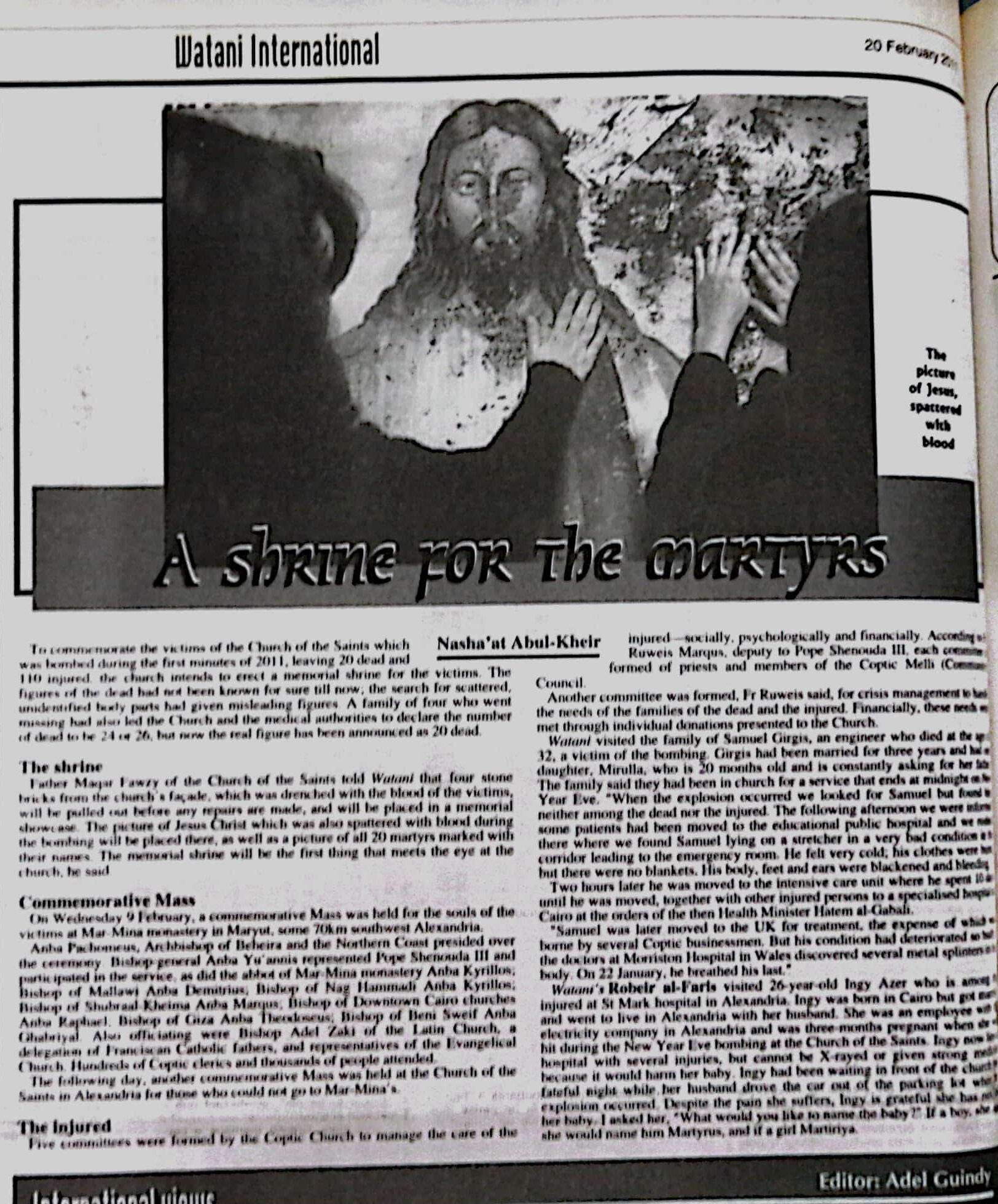

The year started with the heartbreaking tragedy of the gruesome bombing at the church of the Two Saints, known for short as the church of the Saints, in Alexandria, in the first hours of the year. The explosion blew off 24 Copts as they left the church following a midnight New Year service; and injured some 90. The scene was horrifying: body parts and blood flew around; the blood splattering the walls of the church and nearby buildings some 10 metres high.

Even though mainstream Muslims expressed horror at the bombing of the Copts, Islamists—among whom were the Salafis in the mosque across the street from the church—voiced jubilation, publicly sneering at the Copts’ pain.

Even though mainstream Muslims expressed horror at the bombing of the Copts, Islamists—among whom were the Salafis in the mosque across the street from the church—voiced jubilation, publicly sneering at the Copts’ pain.

The Mujahideen electronic web posted threats to Copts, churches, and many Coptic public figures or journalists and intellectuals who, the website claimed, were anti-Islamist. They posted a strongly-worded declaration that read: “This is just the first drop of the torrent”.

Coptic wrath boiled over into the streets of Alexandria, Cairo, and other major cities, railing against the fanatic climate and official inability.

President Hosny Mubarak went on national TV to offer his condolences to Egypt and Copts, saying that “foreign hands” were involved in the explosion incident, and promising that culprits would be dealt with ruthlessly. Before the month closed, Interior Minister Habib al-Adly announced that investigations had revealed that the Palestinian Gaishul-Islam was behind the explosion, in collaboration with local Islamists. Incidentally, no other official explanation has to date been given, neither has any culprit been caught or charged.

Arab Spring

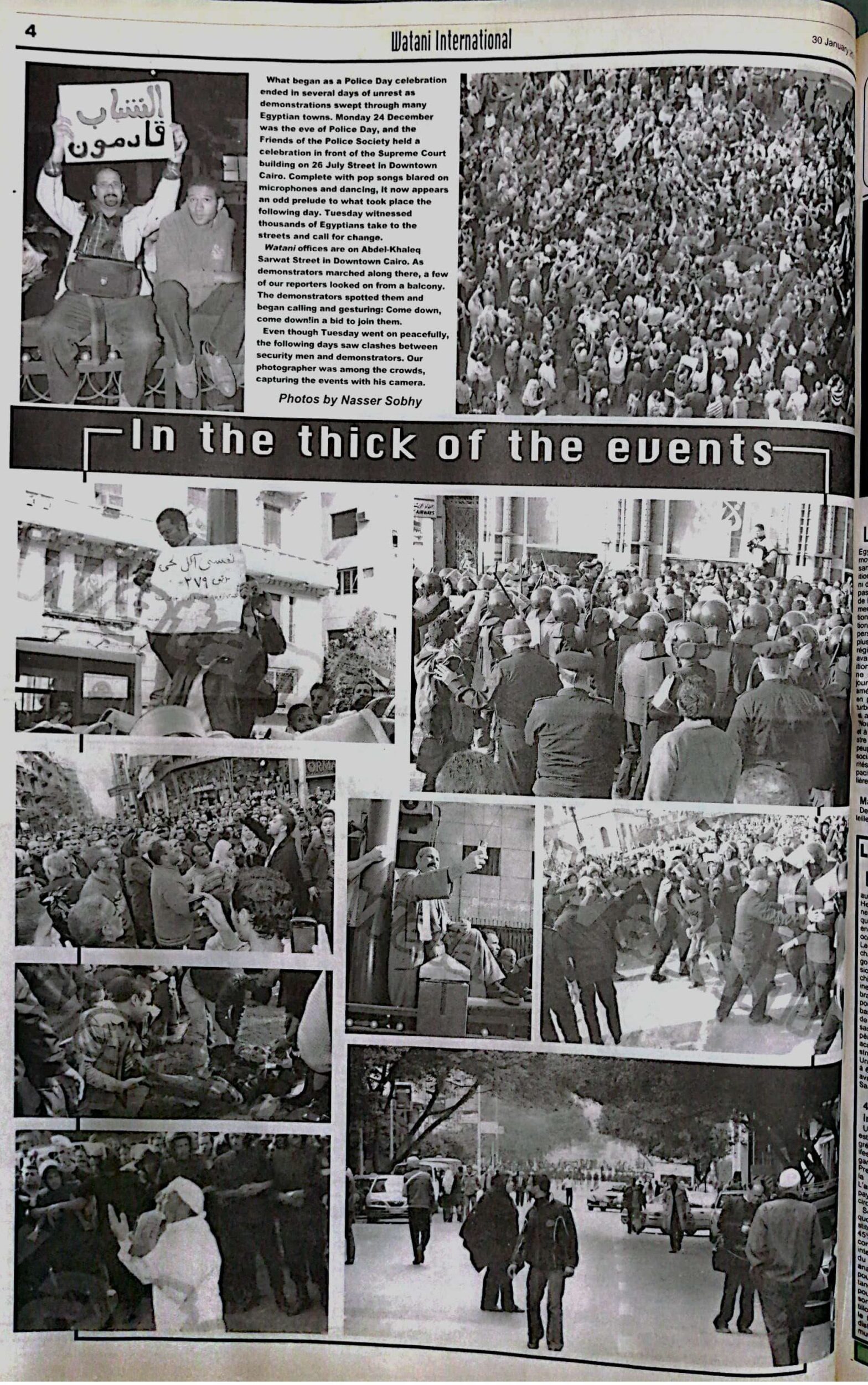

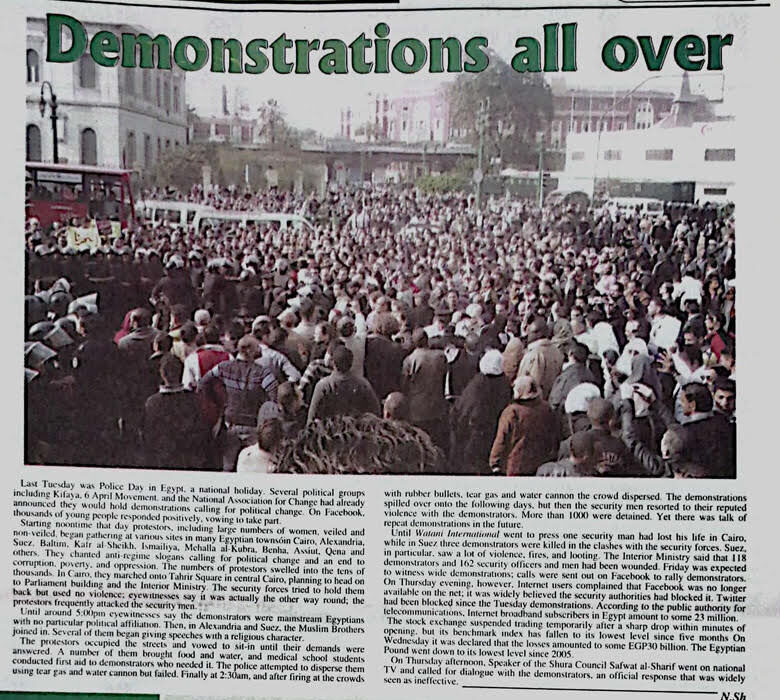

On 25 January 2011, the Arab Spring uprising began with youthful, peaceful demonstrations in Cairo demanding “bread, freedom, social justice”. The police merely kept a watchful eye on the demonstrators until late in the evening when water canons were used to disperse them.

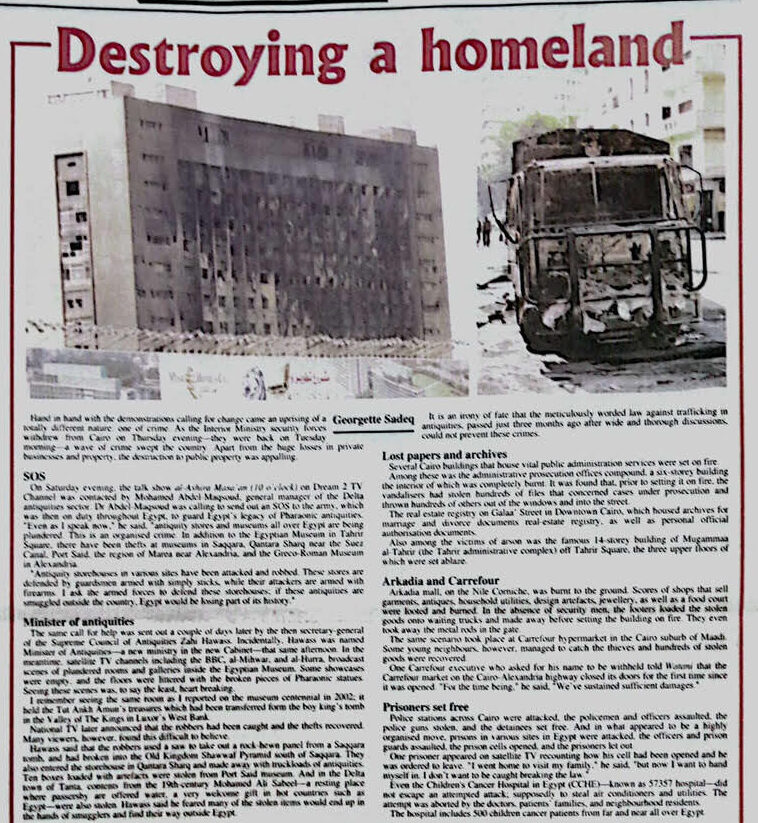

The following Friday 28 January, protestors converged onto Cairo’s central Tahrir Square and on pubic spaces in other Egyptian cities; their numbers swelled, Islamists vocally joined the fray; the demands escalated to more political demands. The protests escalated into an orgy of burning and destruction nationwide. Police stations and public buildings were burned, museums looted, prisons broken into and some 24,000 prisoners let out. The police, defeated and weakened, withdrew and handed the security task over to the military.

That evening, President Mubarak gave a televised address calling for calm, pointing that his term would end in a few months and that neither he nor his son would run for president. He announced changes that met the protestors’ demands, and exhorted all Egyptians to resist destruction of the country. The speech was met by wide public approbation but, the following day, protestors still in Tahrir were attacked by a horse- and camel-riding squad, and shot at by snipers on the roof of the American University in Cairo which overlooks Tahrir; some 11 protestors lost their lives. Today, it has been proved that the attack was organised by the Muslim Brotherhood (MB) but back then rumours attributed it to Mubarak’s regime. This effectively turned the tide against Mubarak; on 11 February he stepped down and handed the country to the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF).

During the 18-day uprising, Watani International also reported on the wide majority of Egyptians who had not gone down to Tahrir, and who supported views other than those expressed in the Square.

The Islamists have come

Once Mubarak stepped down, the Islamist tide, formed in the major part by the MBs and Salafis, started gripping a strong foothold in Egypt, despite resistance from SCAF which attempted to bring on peace till a new president could be elected. However, Egypt went into a spiral of public unrest, lawlessness, an economic nosedive, chaotic media, and brutal attacks against Copts.

Initially, the normally pious Egyptian Muslims were willing to give the Islamists a chance, but the fundamental Islamic practices imposed by the MB and Salafis increasingly drove them out of public favour. A referendum in March 2011 on constitutional amendments widely viewed as Islamist-friendly won a 77.2 per cent vote; the parliamentary elections held in December 2011 and January 2012 amid criticism of rampant irregularities and absent judicial supervision gave the MB and the Salafis around 76.5 per cent of the seats; and when it was time to elect a president for Egypt in June 2012, the MB candidate Muhammad Mursi won by a mere 51 per cent vote.

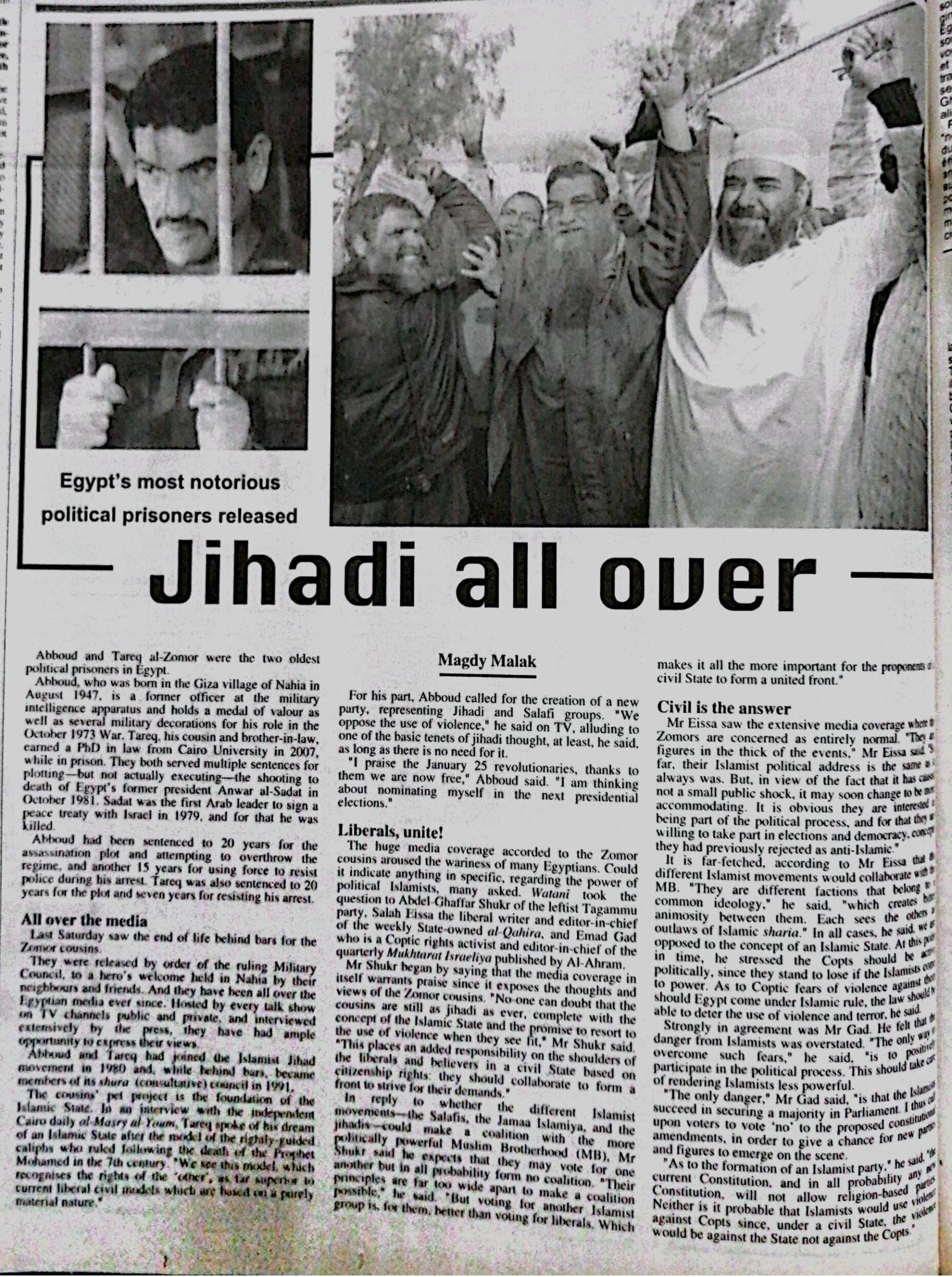

The wave of Islamisation involved releasing from prison Islamist convicts, including the Zomor brothers who were in 1981 complicit in the assassination of President Anwar al-Sadat for making peace with Israel in 1979; one of them declared he would run for president of Egypt.

Islamic hodoud [sharia imposed punishments for specific crimes], even though unlawful, were applied by Islamists, as when a Copt in the southern city of Qena had his ear cut by Salafis for having rented a flat he owned to two young Muslim single women. The MB attempted to set up their own judicial system outside the State system. There were dire attempts to impose the Islamic veil on Coptic women and students; as well as countless attacks against Copts and their churches.

Lawlessness

Egypt descended into lawlessness not seen before by current generations. Public official institutions were set ablaze, destroyed, and looted; this included even courts of law and research centres. Strikes and demonstrations became everyday events, with crime soaring by 200 per cent. Sinai became a tinderbox where Islamist Mujahideen barricaded themselves and spearheaded attacks against Egyptians and against the Israelis across the border.

In September 2011, a several thousands-strong mob attacked and broke into the Israeli embassy in Cairo in response to the killing of five Egyptian policemen in a counter terrorist operation by the Israeli military against Palestinian militants in Sinai who had crossed over the border into Israel and killed eight Israeli soldiers.

In April that year, Mubarak was arrested as were his two sons, and was tried before court on a slew of charges that included killing protestors and corruption. In 2017, following six years in detention, he was cleared of all the charges against him.

Islamism and sectarianism intertwined

The year 2011 was riddled with attacks against Copts, attacks unprecedented in frequency, hatred, viciousness, and coercion. There is only space here to list the most notorious.

Apart from the 2011 New Year bombing in Alexandria, January of that year saw the random shooting at six Copts on a train in Minya, one died and the others were seriously injured. March saw the Copts of the village of Sole, south of Cairo, attacked and their church burned and demolished on allegations of an illicit affair between a Coptic man and Muslim woman; when Copts from Muqattam demonstrated at the injustice, they were met with severe violence that left seven Copts dead, 140 injured, and 15 Coptic homes and workshops burned. In May, the nightmarish attack by a mob of thousands of Salafi Muslims against Imbaba Copts, on account of a rumour that a church in Imbaba was harbouring/imprisoning a Muslim woman convert, left 13 dead, among them eight Copts, and 233 injured.

The massacre

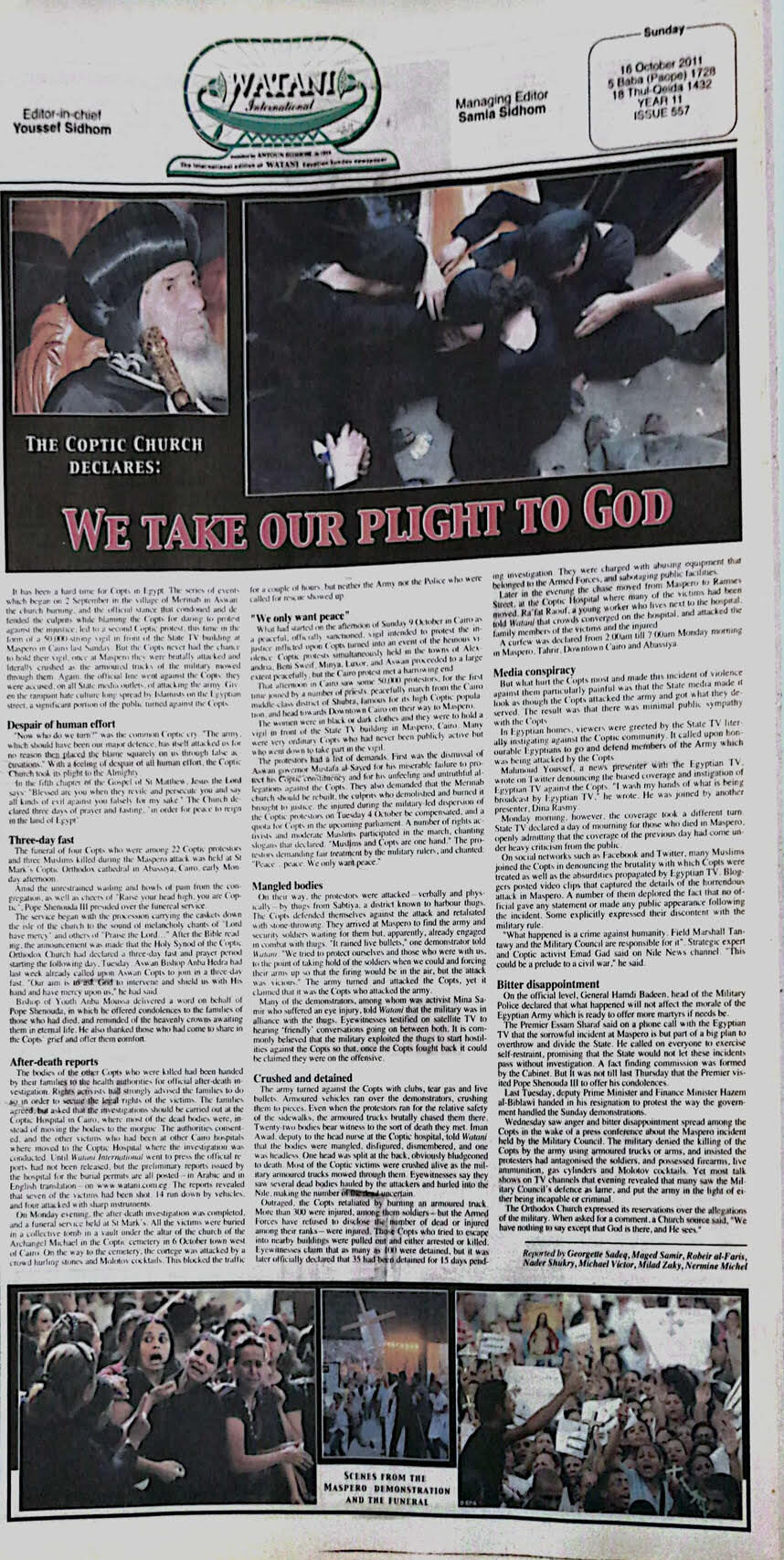

Fast forward to October 2011 to the infamous Maspero massacre of peaceful Coptic protestors. The general rebellion mode Egypt was on had led to the formation of several Coptic NGOs that vocally called for Coptic rights, and to peaceful demonstrations by Copts. September 2011 saw a series of oppressive, humiliating Salafi demands on the Copts of the village of Merinab in Aswan to prevent them from lawfully rebuilding their village church.

The matter culminated in a brutal attack against the Copts and burning of their church. To add insult to injury, Aswan Governor went on national TV to deny there was a church in the first place or that it had been burned. Infuriated Copts organised a peaceful demonstration at Maspero Cairo in front of the TV building in Cairo on 9 October. But they were brutally attacked by army trucks and tanks that literally crushed their bodies to pieces; according to a fact finding commission by the National Council for Human Rights (NCHR), 28 met heinous deaths, and more than 300 were injured.

O my homeland

In “O my homeland” printed on 23 October 2011, Mervat Ayoub sounds researcher and Watani columnist Soliman Shafiq on the situation of Copts then. His reply: “During the period from 1972 to 2010, the number of Copts killed in sectarian attacks against them reached 92, and some 61 were injured. In the first ten months of 2011, the number of Copts killed was 65 and those injured 500; in addition to three churches burned beyond repair, and subsequently rebuilt by the military.”

Incidentally, the SCAF had put forward in May a proposal for a unified law for places of worship in Egypt. Predictably, liberals welcomed the initiative, whereas Islamists unequivocally denounced it. Following initial approval, the highest Islamic authority in Egypt and the Sunni world, al-Azhar, claimed the Muslims had no problem with building mosques so needed no such law; in fact, al-Azhar Grand Imam said, a unified law might place restrictions on the building of mosques. The government, it said, might better issue a law for building churches. Incidentally 2016 saw the enactment of a unified law for building and restoring churches.

The year came to a close as Egyptians headed to the polls for parliamentary elections. No judicial supervision was provided and, amid cries of countless irregularities, preliminary results showed a significant win by the MB.

On cultural front

Amid the momentous incidents taking place in 2011, a few cultural and social events found their way into our paper. The issue of 23 January carried a story about famed Egyptian British cardiologist Sir Magdi Yacoub being decorated with the prestigious Nile collar for the Arts and Sciences; 8 May featured a piece on a cache of singular art works found buried in a vault underneath the Museum of Egyptian Civilisation in Gezira, Cairo; 24 July 2011 held an obituary for French Egyptologist Christiane Desroche Noblecourt (1913 – 2011) famous for her outstanding efforts to save the ancient Egyptian temples that would have drowned under the High Dam reservoir waters in the 1960s; and 18 December commemorated 100 years on the birth of Nobel Laureate novelist Naguib Mahfouz.

The above review represented a read in Watani International’s 2011 issues. It was not feasible to cite in detail each and every article from which the information was taken, nor the names of the writers and reporters. Almost every single article during that year is worth a read.

In order to give credit where credit is due, I cite the names of the Watani staff who covered the events, listed alphabetically by first names:

Adel Mounir, Erin Moussa, Fady Labib, Georgette Sadeq, Hanan Fikry, Hany Danial, Ikhlass Atallah, Injy Samy, Lillian Nabil, Magdy Malak, Maged Samir, Mariam Adly, Mervat Ayad, Mervat Ayoub, Michael Victor, Milad Zaky, Mina Zakariya, Nabil Adly, Nader Shukry, Nash’at Abul-Kheir, Nasser Sobhy, Nermine Michel, Nevine Kameel, Robeir al-Faris, Samia Ayad, Samira Mazahy, Sanaa’ Farouk, Shaimaa’ al-Shawarby, Soliman Shafiq, Talaat Radwan, Tereza Kamal, Victor Salama, Wissam Abdel-Alim

Watani International

12 September 2021