Given that Watani International is this year marking 20 years in print—our first issue was printed on 18 February 2001—we have promised our readers to publish every month a review of our issues in two successive years. We already reviewed the issues from 2001 to 2008; today we keep good on our promise by covering 2009 and 2010. The reader is advised to read this review bearing in mind that the first month in the following year, January 2011, would bring about the Arab Spring uprising and the subsequent rise to power of the Muslim Brotherhood (MB). This rise, in fact, was a process that had begun around 2005 / 2006 and escalated throughout the years following.

Islamists on Egypt’s eastern border

Flipping through the pages of Watani International’s 2009 and 2010 issues brings into full focus the turbulent political climate in Egypt. In hindsight, that turbulence was a precursor to the 2011 uprising known as the Arab Spring which featured heavy Islamist presence.

Islamists had been on Egypt’s eastern border ever since Hamas won parliamentary elections in Gaza in 2006 then took over in 2007—Hamas is the Palestinian arm of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood (MB). Hamas was attacking Israelis, and Israel promptly counterattacked. The conflict spilled over into Egypt as hordes of Palestinians attempted to flee Gaza by crossing the border into Egypt. This led Egypt to close its border crossing at Rafah, opening it only at specific times to allow in Palestinians who needed critical help, and to send relief aid to Gaza. Most Arab countries criticised Egypt harshly for closing its border, even though none lifted a finger to help the Gazans.

At the same time, Egypt was already battling Hamas on another front: the underground tunnels which Gazans continued to build to connect Rafah to Gaza. These tunnels acted as conduits to smuggle arms, goods, and people. Since Egypt was bound by its 1979 peace treaty with Israel to post a limited police force in Sinai, it was unable to put an end to this problem; the Palestinians and their accomplices built more tunnels than Egypt managed to destroy. Egypt feared Hamas would infiltrate Sinai so that Egyptians would be plagued with an Islamist battlefront on their land; which incidentally did occur following the 2011 Arab Spring when the MB rose to power and allowed jihadi groups such to barricade themselves in Sinai.

It did not help that the Sinai Bedouin were at loggerheads with Egypt’s police on account of the rampant outlaw activity they were notorious for, not least for smuggling people, drug, and arms. The entire problem was analysed by Israeli affairs expert Emad Gad in an interview with Watani’s Nader Shukry printed in Watani International on 25 January 2009 under the title “Exporting the problem to Egypt”; also in a piece titled “The issue of a wall” by Mervat Ayoub on 17 January 2010; and “Bedouin predicament” by Maged Samir on 8 August 2010.

President Obama visits Egypt

On 1 March 2009, Maged Samir reported, under the title “Why hurt the tourists?” on a terror incident in Cairo’s famed Khan al-Khalili bazaar where a bomb exploded in a coffeeshop killing a 17-year-old French girl who was visiting Egypt with a group of French teenagers, and injuring 25 tourists and Egyptians. The MB hastened to deny it had any hand in the incident, and said that neither did Hamas. Yet it was done by Islamist individuals under the influence of fundamentalist propaganda and anger at the “inadequate” Egyptian stance vis-à-vis the Palestinians.

June 2009 saw US President Barack Obama visit Egypt and extend a peaceful hand to the Islamic World from Cairo University’s venerable Assembly Hall. It was an attempt to put an end to the clash of civilisations that had erupted in the wake of 9/11, and to work conciliation between the US and Muslims worldwide. In anticipation of the visit, Magdy Malak wrote under the title “Great expectations” sounding political expert views on the topic. Ironically, Islamic rule came to Egypt three years later on the wings of the Arab Spring, strongly supported by the US and the western world.

Call for change

Egypt was on the threshold of parliamentary elections in 2010 and presidential elections in 2011. The climate was one of general discontent; harsh vociferous criticism of incompetence, corruption, and despotism attributed to the ruling regime; and demonstrations, protests, and strikes escalated by the day. There was a vocal call for change.

On 28 February 2010, Watani International printed an interview by Hany Danial with human rights activist Ahmed Kamal Abul-Magd who said Egypt was in need of “A white revolution”; Dr Abul-Magd was nonetheless famous for his Islamic leanings. On 21 November 2010, Watani’s Samia Ayad interviewed prominent Coptic politician and industrialist Mounir Fakhry Abdel-Nour on “The arduous road to reform”.

The MB were gaining a solid foothold on the political arena by playing on public sentiments of the need for change and exasperation with rampant corruption, and by luring the normally pious Egyptians with the concept of a regime that ruled according to the teachings of the Qur’an. Realising that Copts represented a voting bloc to be reckoned with, the MB went out of their way to woo Coptic votes. Conflict among their conservative and more modern ranks was surfacing, but it was only a difference on the effective means to gain power, not the end. After all, the basis on which they would rule stood on solid fatwas—a fatwa is an Islamic legal edict—which they could not contradict. This was reported in Emad Nassif’s “The Brotherhood’s new face” on 21 February 2010, expertly analysed in Watani International’s 25 July 2010 issue by analyst Abdel-Rehim Aly under the title “The MB on Copts: more equal than others”; and by Robeir al-Faris’s “How far Islamisation?” on 5 September 2010. Predictably, liberals fought back. On 19 September 2010, Faris reviewed, under the title “The road to violence” Wahid Hamed’s serial TV drama Al-Jamaa that bared the MB since the movement was formed in 1928 at the hands of Hassan al-Banna (1906 – 1949), exposing their history of initial charity works that paved the way to violence and a string of political assassinations.

Quotas: yes for women, no for Copts

For the first time, and in preparation for parliamentary elections in November 2010, women were granted a quota in Egypt’s parliament. Magdy Malak wrote on 28 June 2009 on “The woman’s share”, reviewing the history of women on the political scene, and sounding the opinion of political analysts on the quota. Most thought it was controversial and preferred that women would run on a slate system, but there was general agreement that the move was positive. Extending the case to Copts as a marginalised group that warranted positive discrimination, however, gained almost no support even among liberal politicians who claimed that whereas women made 50 per cent of the community, Copts were a minority.

On 31 October 2010, Adel Mounir wrote “Women in Egypt’s Parliament: Ready for the race”, a report card on women’s contribution to parliament; an impressive report card indeed.

Elections

Come November 2010, parliamentary elections were held with much electioneering online, a first in Egypt, and under widespread cries of foul play. In December, preparations were being made for the runoff elections, but there was not much hope for the MB, which had had 20 per cent of the seats in the previous parliament, nor for opposition parties. On 5 December 2010 Watani International printed a piece by Adel Mounir under the sarcastic title “Who needs the opposition?”

In the meantime, Egypt was also anticipating the presidential race in 2011. Even though the Constitution allowed for multiple candidate election, a candidate who ran independently without party support had to fulfil conditions not easily attainable. One candidate stood out, however: Mohamed ElBaradei, the Egyptian former head of the International Atomic Energy Agency who, despite long years away from Egypt, came back in February 2010 with the intention of running for President to bring about the aspired change. But following initial public enthusiasm for Mr Baradei, he lost popular and political support. The public felt he was out of touch, and the political parties interpreted his refusal to collaborate with them as arrogance. On 28 February 2010 and on 14 March 2010 respectively, Magdy Malak wrote on Mr Baradei’s homecoming “Making a difference”, and Emad Nassif on his “Presidential ambitions”.

A man killed

An incident occurred in June 2010 which was later deemed pivotal in playing out the Arab Spring uprising in January 2011. That was the killing of 28-year-old Khaled Said on 6 June 2010 in Alexandria at the hands of two security officers. Said was a drug addict and dealer who was well known to the police. On the day he died, he was being chased by two plainclothes policemen. Once they caught him, he attempted to swallow the drugs in his possession; they tried to force him to spit them out and cruelly beat him up in the process. He choked on the drugs and died, possibly also of the brutal hits on his face and jaws. The incident was taken to embody everything that was wrong with the ruling regime, and everything that ought to change. Public anger seared, and protests ran the streets for several days, condemning a system that allowed such police brutality. Maged Samir and Samira Mazahy reported on the issue on 27 June 2010, under the title “A man killed”. Said became the “hero” of 2011 uprising.

Culling the pigs

Against the turbulent backdrop, a plethora of political and sectarian incidents took place.

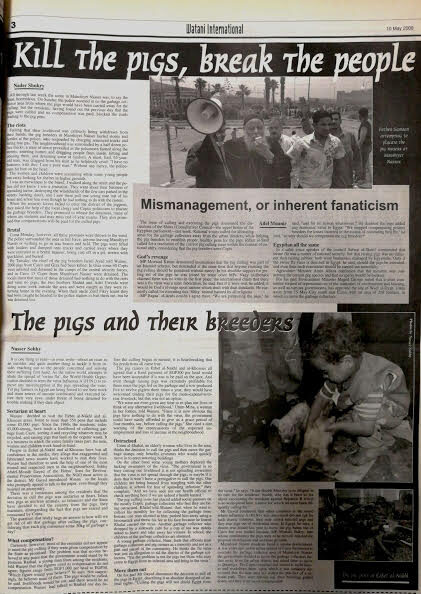

Watani International reported on the swine flu (H1N1) outbreak in 2009 which, despite facts that the virus did not move from pigs to humans, led Egypt’s parliament to acquiesce to Islamic influence and decree the killing of the country’s pig population. Pigs are “impure” animals in Islam, so were raised by Copts, notably the Coptic community of garbage collectors who then suffered greatly by the pig culling which was moreover executed in an appallingly cruel manner. On 10 May 2009, Nader Shukry wrote “Kill the pigs, break the people” and Nasser Sobhy “The pigs and their breeders”; on 17 May 2009 Ishaq Ibrahim wrote “It’s not the pigs, stupid” meaning the culling had nothing to do with the pigs which, after all, did not carry the disease, but with religious fanaticism; and on 14 June 2009 Georgette Sadeq covered the health situation with “H1N1 hits”.

A year later, on 29 August 2010, Mervat Ayoub wrote “No meat for the poor”, reporting on the leap in price of meat, which many attributed to the decrease in supply on the market since the pigs were culled.

Harrowing crimes against Copts

On the sectarian front, attacks against Copts escalated in number and viciousness. Hardly a week passed without some attack taking place. Many were blatant hate crimes in which the police was frequently complicit, easily incited by the Islamic current. They came under pretexts which ranged from personal disputes-turned-collective “punishment” against Copts to the thorny issue of de-facto churches or church building rejected by the Muslim community. The purpose was obvious: attacks against Copts, and in two cases against Baha’is, not only fed the rising fanaticism, but effectively worked to destabilise the country. For the MB and their supporters, it was win-win.

The titles tell it all.

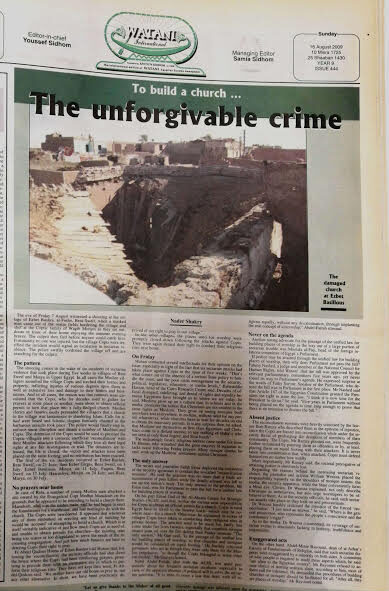

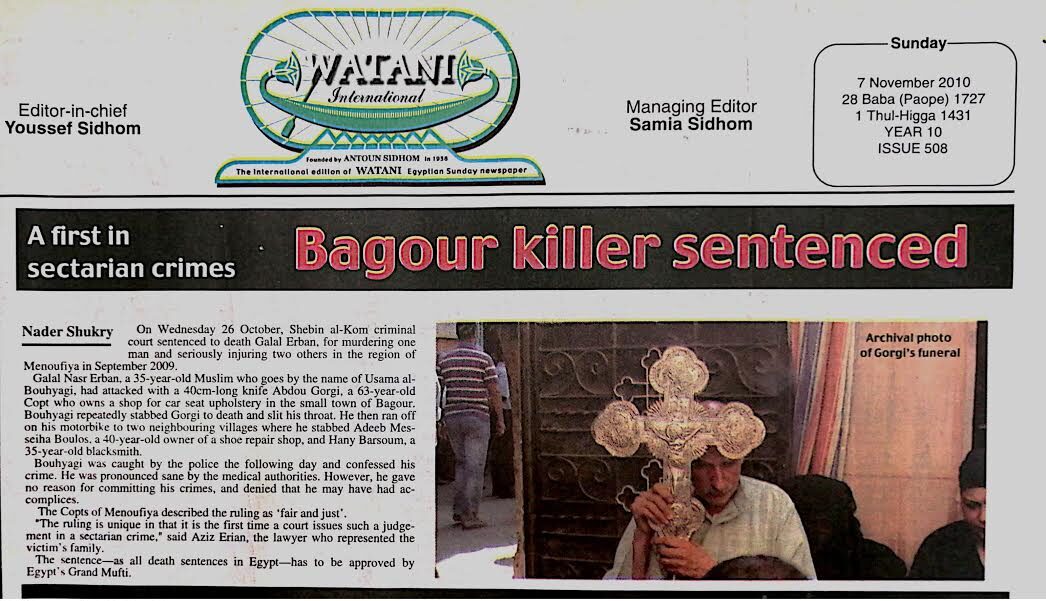

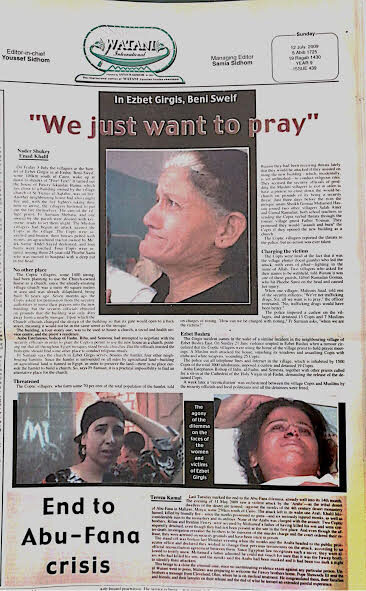

Throughout 2009 and 2010 Watani International printed coverage of attacks of sectarian nature by Nader Shukry, Nasser Sobhy, Robeir al-Faris, Adel Mounir, Teresa Kamal, Nash’at Abul-Kheir and Emad Khalil under the titles: “Punishment for no crime”, “We are all Baha’is”, “Deir Abu-Hennes remains Deir Abu-Hennes” [On official attempts to change the village’s age-old Coptic name; the villagers rebelled and retained the name], “We just want to pray”, “Where victims are turned into suspects”, “No place to pray”, “Sixth Attack [against Copts in Minya village] in five weeks”, “Bombs at the cathedral”, “To build a church: the unforgivable crime”, “Sectarian strife in Egypt: Swept under the carpet”, “Horrendous crime [Copt slaughtered] in Bagour [the killer was 11 months later sentenced to death] , “A church is burnt”, “Killings in Minya”, “Where to bury a dead Copt”, “One errs thousands pay”, “Train tragedy”, “Bloodshed on Christmas Eve”, “Three days in hell”, “Seven houses burnt”, “Crying against injustice”, “Live ammunition against Copts”, and many others.

Out of church boundary

Among all the painful attacks against Copts, two stood out. One was the drive-by shooting at Copts in the town of Nag Hammadi some 570km south of Cairo, which targeted Copts as they left church following Christmas Eve Midnight Mass, six Copts and one Muslim passerby lost their lives, and 14 were injured. Incidentally, the killer Hamam al-Kamouni was sentenced to death and executed in October 2011.

The other incident occurred in November 2010 and involved clashes between Giza Copts and the police over the building of a church in Umraniya, Giza, without licence.

The two incidents led to an unprecedented response by the Copts. Instead of their usual protest inside church grounds, the Copts went out to peacefully protest in front of Parliament and, in the Umraniya case, at Giza Governorate headquarters. For the first time, police used live ammunition against the Copts; three Copts were killed, 100 injured, and 157 detained by the police for “rioting”.

In the meantime, the escalation against Copts, which in many cases owed to their building unlicensed churches because obtaining license was a lengthy decades-long process that stripped them of all dignity and would normally end in no licence, drew public attention to that bitter problem. Given that mosques needed no licence whatsoever, and were moreover granted all facilities, liberals in Parliament called for a unified law for places of worship in Egypt. Adel Mounir and Nader Shukry wrote about the issue on 25 October 2009 under the respective titles: “Building on prejudice” and “Not by law alone”.

Pope meets President

The year came to a close with one positive move: a meeting between Pope Shenouda III and President Mubarak. The meeting was apparently beneficial; even though neither the presidency nor the Church commented, the Pope emerged visibly relaxed and content. The Umraniya detainees were all released. Nader Shukry covered the meeting on 26 December 2010 under “The Pope meets the President”.

Holy Virgin of Warraq

Given that this story has become too long, the reader will forgive me for simply jotting down other important coverage without going into details.

In June 2010, a court order was issued obliging the Church to remarry civilly divorced couples. Pope Shenouda answered by saying that the Church must “Obey God not man” as reported by Adel Mounir on 13 June 2010. Watani International elaborated on the topic with an article by Fr Yuhanna Fayez on 27 June 2010 “What God has joined let no man separate”.

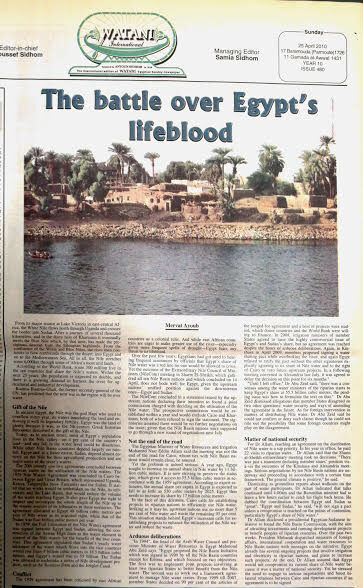

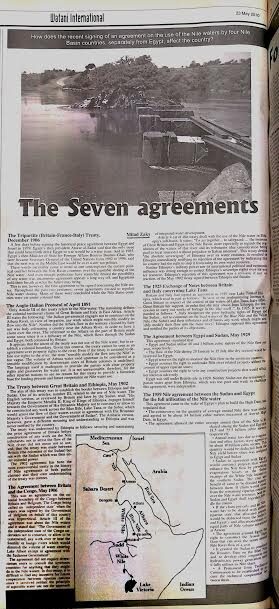

Issues of April, May, and June 2010 carried coverage on the start of disputes between Egypt and Nile Basin countries over Nile waters; 15 March 2009 featured an elaborate file on healthcare in Egypt, 25 July 2010 another on education; 11 June 2010 on controversy over teaching ethics vs teaching religion in schools.

20 December 2009 on manifestation of the Holy Virgin on the domes and cross of her church in Warraq, Giza; 7 June 2009 an interview by Victor Salama with Metropolitian Anba Bishoy (1942 – 2018) on the Coptic Church’s efforts in the ecumenical council at the Vatican, and 4 January 2009 an interview with Swiss researcher and writer Christine Chaillot who wrote a series of books on the various Oriental Orthodox Churches, beginning with the Coptic Church.

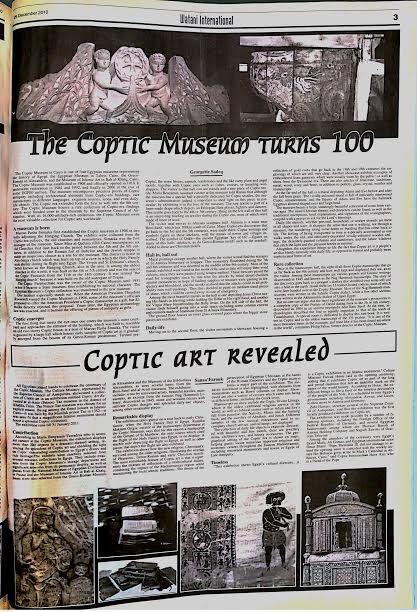

Centenaries, jubilees, and special topics were celebrated: 2 August 2009 carried a story on the 75th anniversary of Egyptian Radio; 21 February 2010 one on 200 years on the epic tome “Description de l’Égypte” written by French scholars who accompanied Napoleon’s military campaign against Egypt in 1798 – 1801; 26 December 2010 “The Coptic museum turns 100”; 15 August 2010 “TV’s golden jubilee”; 27 September 2009 “The Egyptian Academy of Art in Rome” [following a five-years renovation]; and 2 May 2010 “Half a century in the dance” on the first Egyptian folk dance group: the Reda Troupe.

Centenaries, jubilees, and special topics were celebrated: 2 August 2009 carried a story on the 75th anniversary of Egyptian Radio; 21 February 2010 one on 200 years on the epic tome “Description de l’Égypte” written by French scholars who accompanied Napoleon’s military campaign against Egypt in 1798 – 1801; 26 December 2010 “The Coptic museum turns 100”; 15 August 2010 “TV’s golden jubilee”; 27 September 2009 “The Egyptian Academy of Art in Rome” [following a five-years renovation]; and 2 May 2010 “Half a century in the dance” on the first Egyptian folk dance group: the Reda Troupe.

Books

Notable among the coverage offered by Watani International in 2009 / 2010 was a number of book reviews. These included a book written by Helene Moussa and published by St Mark Coptic Museum in Toronto on 20th-century artist Marguerite Nakhla.

Also a series of books published in Arabic by Watani in 2009 and 2010, which each tackled a significant Coptic issue or event written by Watani journalists specialised in the respective topics. The Watani Book titles reviewed included “Days of Pain and Triumph” by Robeir al-Faris on the days in 1981 spent in prison by the Coptic bishops and priests imprisoned by President Anwar al-Sadat among more than 1,500 cultural, intellectual, and anti-Islamist figures he saw as dissidents one month before he was assassinated by Islamists on 6 October 1981; and “Sweeping the law aside” by Nader Shukry on the infamous ‘conciliation sessions’, traditional out-of-court settlement of disputes by village elders, which implicitly implied renouncing legal rights, and which in the case of Copts invariably imposed on them intolerable pressure and harsh, oppressive terms of settlement.

There were also Watani Books on the history of Copts in Egypt’s parliament written by Adel Mounir; Copts’ conspicuous absence from the public sports field by Nour Qaldas; Egyptian women inside and outside the sphere of the family by Laila al-Hinnawy; a Christmas gift book by a group of young Watani journalists, books on two significant Watani figures: Antoun Sidhom and Mossaad Sadeq; and a book on the manifestations of the Holy Virgin in Egypt by Victor Salama.

Obituaries

During 2009 and 2010, Watani International wrote about persons who passed away leaving behind significant contributions. These included Egyptologist and writer Erian Labib Hanna (1936 – 2009); Islamic thinkers and writers Mustafa Mahmoud (1921 – 2009) and Amin Huweidi (1922 – 2009); Princess Feryal (1938 – 2009); Coptic activist (Adly Abadir 1920 – 2009); al-Azhar Grand Imam Sheikh Sayed Tantawi (1928 – 2010); novelist and playwright Usama Anwar Okasha (1941 – 2010); and progressive Islamic philosopher Nasr Hamed Abu Zeid (1943 – 2010) who self-exiled out of Egypt once he was declared an apostate and ordered to divorce his Muslim wife.

Watani International

8 August 2021