The date 11 September 2020 marked the first day of the Egyptian New Year, 1 Tut 6262, and the first day of the Coptic New Year, 1 Tut 1737.

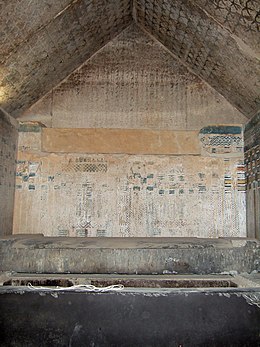

Both calendars are one and the same since they have a common root: the ancient Egyptian calendar that started, according to Egyptological studies, 6262 years ago. Numerous ancient inscriptions and texts refer to the Egyptian calendar; among them texts in Unas Pyramid, built in Saqqara in the 24th century BC.

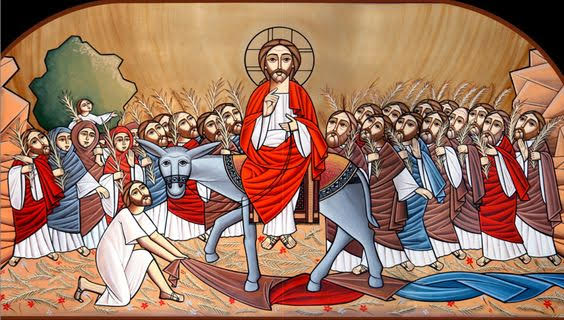

The Coptic calendar, however, began its count in AD284, the year the Roman Emperor Diocletian’s reign began. Under that emperor, thousands of Egyptian Christians—Christianity was brought into Egypt by St Mark in the first century; he was martyred in Alexandria in AD68—were harshly persecuted, tortured, and martyred on account of their faith which they refused to renounce. The horrendous bloodbath, an explicit statement of the staunch faith of Egyptians, was so engraved in their minds, that they began counting their years with the year Diocletian ascended the throne. A new year-count thus started; it was aptly named the Anno Martyrum (AM) calendar, the calendar of the martyrs.

To this day, Egypt’s Church terms itself the Church of the Martyrs, and uses the AM calendar to mark its history, events, and worship. It celebrates the New Year with Vespers and Mass, also joyous prayer and hymns, famous among them is the refrain: “Lord, crown this new year with the blessings of Your goodness” (Psalm 65: 11). Copts feast on red dates which are then in season, seeing the red to denote the martyrs’ blood, the white heart of the date as the pure hearts of the martyrs, and the hard stone inside to symbolise their strong faith.

The Nile and stars

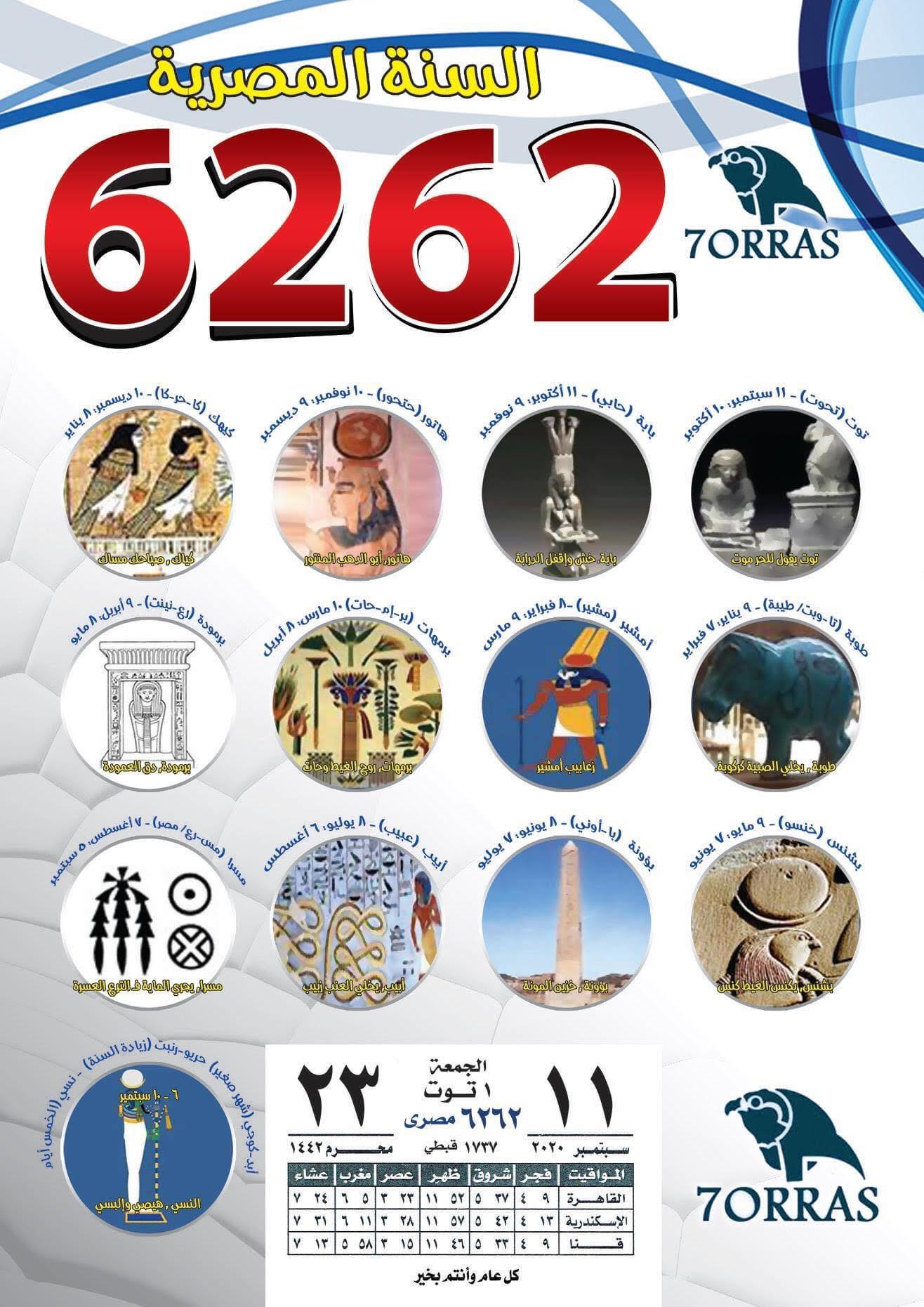

The Egyptian year is a stellar one that begins on the day the star Sirius, Sopdet in Egyptian, appears on the horizon together with the rising sun. It includes 365 days, a leap year is 366 days, and is divided into three seasons of four months each, which feature the Nile’s annual flood that inundates the land, the sowing and cultivation season, and the harvest. The year includes 12 months of 30 days each, plus a “small month” of five days in a simple year and six days in a leap year.

Sopdet (Sirius) appears in specific points in the sky throughout the year. Its appearance in the centre of the sky at night on 12 Pa’ouna (19 June) coincides with the beginning—the First Drop—of the Nile flood, a day that was celebrated as a great feast; today the Coptic Church celebrates it as the feast of the Archangel Michael, patron saint of the River Nile. When Sopdet appears with sunrise on 1 Tut, it heralds in the New Year.

In rural Egypt, the rigorously accurate Egyptian calendar is the only one used to mark annual changes and events concerning the Nile, agriculture, and the climate. Its months, derived from names of Egyptian gods and goddesses, are each denoted with a popular folk saying that focuses on its main feature or activity. The first month, Tut which coincides with September/October, is named after the god of wisdom Thoth and coupled with the saying: Tut tells the [harsh summer] heat to die. Kiahk which coincides with December/January, the shortest days in the year, is denoted with: In Kiahk, your morning runs into your evening; before you have lunch prepare your supper. And Abib, July/August is described as: Abib turns the grapes into raisins.

According to Historian James Henry Breasted (1865 – 1935), the Egyptian calendar was carried by Julius Caesar to Rome and used as the most precise calendar, the precursor to the current Gregorian calendar.

Official disuse, Coptic commitment

The Egyptian New Year went into official disuse in the 19th century when Egypt’s ruler, Khedive Ismail, decided to replace it with the Gregorian calendar widely used by the western world. The West and the world at large knew nothing of the Tut calendar, so the Khedive decided to replace it with the ‘western’ AD chronicle. That was in 1591AM which coincided with 1875AD.

Many Egyptians, however, to this day feel alien to the Gregorian calendar and are not well familiar with the names of the months, so it is very common to hear these months defined by their ‘number’ on the calendar. January is Month One, April is Month 4, October is Month 10, and so on.

Today, the Egyptian New Year is marked by not many people in Egypt, but their numbers are steadily on the rise. Raising awareness of the Egyptian identity, which has been downplayed for centuries in favour of religious [Islamic] identity, is now being revived and increasingly promoted by NGOs and intellectuals concerned with regaining authentic Egyptian values.

For Huraass al-Hawiya al-Misriya, literally Guardians of the Egyptian Identity (GEI), the Egyptian New Year is a very significant event that calls for fitting celebration. Samy Harak, founder of GEI, says the NGO started celebrating the Egyptian New Year back in 1997 by printing the Egyptian calendar and distributing it around; they have continued to do so every year.

Mr Harak lauds the Copts for adhering to the Egyptian calendar, saying they never gave it up even when they took up Christianity as a religion, in the light of which the Egyptian calendar might have been seen as some pagan relic. “They respected and held on to their roots,” he says.

In pharaonic apparel

This year, in what has become an annual tradition, the NGOs Coptic Heritage Lovers and the GEI celebrated the New Year with a felucca cruise in the Nile; Egypt’s lifeblood so intricately connected to the calendar. They sang and danced, and ate red dates. A group of Alexandrians came to Cairo, visited their ancestors in the Egyptian Museum in Tahrir Square, then joined the New Year celebration. Participating in the celebration were Egyptian writer and activist Fatima Naoot; and veteran writer and GEI member, Talaat Radwan.

Another celebration was held by the Association for Preserving Egyptian Heritage (APEH) in cooperation with Kemet Foundation, ‘Kemet’ is the ancient Egyptian name for the land of Egypt. The celebration featured a bus tour through Cairo streets; the bus was emblazoned with the banner: Egyptian New Year 6262. They were joined by other associations concerned with Egyptian Heritage. APEH’s female members were dressed in ancient Egyptian apparel, and a large number of public figures participated. Among them were Dr Gameel Ebeid, head of Kemet Foundation; and members of the board of APEH including Alaa Bahnassy, coordinator of the celebration.

For five hours, from 5pm to 10pm, the tour started in the North Cairo district of Shubra, proceeded to the central Cairo squares of Tahrir and Ramses, and on to the eastern Cairo suburb of Heliopolis. Along the way, it was met on its many stops by a warm welcome from the public, with many taking selfies with APEH members in pharaonic dress.

Cards that carried information about the Egyptian New Year and calendar were distributed to the people in the street, who eagerly looked through them.

The NGOs concerned with Egyptian identity hold regular seminars and activities all year round in various places in Egypt to familiarise people with their magnificent Egyptian heritage.

”Crown this year with Your blessings”

The Coptic Church honours the New Year of the Martyrs with the Nayrouz feast. There is a common error that the word derives from Persian; rather, it goes back to the ancient Egyptian ‘Ni Yaro’ (feast of the rivers) and denotes the ancient celebration of the Nile flood.

The dates and months of the Egyptian year are intricately woven into Coptic worship. Coptic Mass includes special requests, awashi in Coptic, to the Good Lord for blessings, which rotate with the seasons. During the inundation, the Church prays: “Bless the waters of the River, raise them as is proper, according to Your goodness”; too high or too low a flood was, before the 1970 Aswan High Dam, both detrimental to life in Egypt. In the sowing season, prayers are said for the plants and trees, to “grow and be fruitful”; and in the harvest season, for “the winds of the skies and the fruits of the earth”. In typical Egyptian sentimentality, the prayers for the winds, which during that season include the hot, hated khamaseen sandstorms, are worded: “Bestow a good mood upon the winds”, and the prayers for the earth are worded: “Let the face of the land be joyful”.

Along the same line, the Bible reading during Mass in the first two Sundays of the month of Hatour (November/December) are those of the “sower [who] went forth to sow.” This time coincides with the sowing season following the recession of the flood waters.

And during the last two Sundays of every Coptic year, the Bible readings are those of the end of the world—a reminder, as the year ends, that our own lives will come to an end. But then again, the New Year hails, and the Church prays: “The old has passed away, all things are become new” (2 Cor 5: 17).

Watani International

16 September 2020